Why the Gulf is Betting Big on America: Inside the $3.2 Trillion Investment Wave from KSA, Qatar, and UAE (2023–2025)

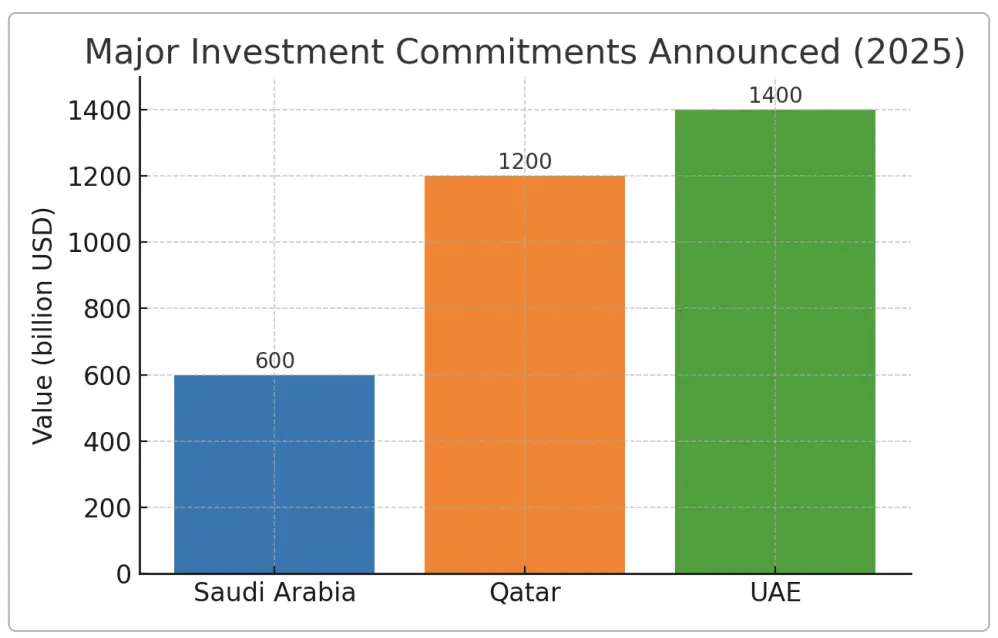

Between 2023 and May 2025, the Gulf states of Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates have dramatically expanded their investment footprint in the United States, culminating in several unprecedented investment pledges around May 2025. These include Saudi Arabia’s commitment of approximately $600 billion in commercial deals with the U.S, Qatar’s agreement targeting an economic exchange of $1.2 trillion (with $243.5 billion in immediate deals), and the UAE’s announcement of a 10-year, $1.4 trillion investment framework in the U.S. These headline figures dwarf the current scale of realized Gulf investment in the U.S. – by end of 2023, Saudi FDI stock in the U.S. stood at only about $9.6 billion, Qatar’s at $3.3 billion, and the UAE’s at $35 billion. The surge in commitments reflects both Gulf states’ strategic push to diversify their oil-based economies and the United States’ receptiveness to Gulf capital for bolstering domestic industry and innovation. Major deals have focused on high-impact sectors such as aerospace (e.g. record Boeing aircraft orders), defense technology (e.g. cutting-edge drone and counter-drone systems), artificial intelligence and tech (from joint AI infrastructure projects to quantum computing ventures), clean energy and infrastructure (from LNG export terminals to new manufacturing plants), and more. Investment vehicles like Saudi’s Public Investment Fund (PIF), Qatar Investment Authority (QIA), and Abu Dhabi’s sovereign wealth funds are driving these deals, often in partnership with U.S. firms or funds.

The motivations behind these investments are multifaceted. For Gulf nations, pouring capital into the U.S. secures financial returns and technology transfers vital for their long-term economic visions (such as Saudi Vision 2030 and Qatar National Vision 2030), while also strengthening geopolitical alliances with Washington. For the U.S., Gulf investments promise to create jobs, fuel innovation, and finance new industrial capacity on American soil, at a time when competition for global capital is intense. The economic impact of realized deals is already significant – for example, Qatar’s $96 billion Boeing order is expected to support over 1 million U.S. jobs during production, and UAE’s new aluminum smelter would double U.S. aluminum output. However, these partnerships also raise regulatory and strategic considerations. U.S. authorities are balancing the inflow of Gulf capital with national security reviews (CFIUS) for investments in sensitive sectors like semiconductors and defense, and observers caution that political controversies (e.g. human rights issues or Gulf rivals’ influence) could affect public perception of these deals. Notably, Gulf commitments often come as memoranda of understanding or long-term pledges, meaning a risk of unrealized commitments if economic or political conditions shift.

Overall, Gulf investment into the U.S. from 2023 through May 2025 marks a historic upswing both in scale and scope. This report provides a comprehensive analysis of this trend – from the historical context of U.S.–Gulf economic ties to the breakdown by country, sector, and strategic motive. It finds that while actual investment inflows so far remain moderate relative to grand announcements, the flurry of 2025 deal-making represents a deepening interdependence: Gulf states are now key investors in America’s future industries, and the U.S. is increasingly intertwined with Gulf economic diversification. Opportunities abound – in financing the energy transition, advancing AI, and mutually boosting prosperity – but so do challenges in managing security concerns, market risks, and ensuring that pledged investments translate into tangible outcomes. The stage is set for a new era of Gulf-U.S. economic partnership, one that could reshape both the American industrial landscape and the Gulf’s global strategic positioning in the years ahead.

Introduction

Purpose and Scope: This report examines major investments by the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) into the United States between January 2023 and May 2025. It places a special emphasis on landmark developments and announcements made in and around May 2025, a period that saw Gulf investment pledges to the U.S. reach extraordinary heights. The analysis covers historical context of U.S.–Gulf economic relations, detailed breakdowns of investments by each of the three countries, and thematic sections on motivations, impacts, geopolitical context, regulatory considerations, and future outlook. While the primary focus is on Gulf capital flowing into the U.S., the report also briefly notes U.S. investments in the Gulf to provide reciprocal context.

Methodology: Research for this report draws on a wide range of sources, including official government statements and fact sheets, sovereign wealth fund disclosures, financial and industry news (e.g. Reuters, Bloomberg), think tank analyses, and academic commentary. Key data points such as foreign direct investment (FDI) stocks and major deal values are sourced from U.S. Department of Commerce data and verified news reports for accuracy. The report distinguishes between **“committed” investments – pledges or agreements that have been announced – and **“actualized” investments – funds that have been materially deployed or realized. All monetary values are in U.S. dollars. To enhance clarity, important figures are presented in tables and charts, and all factual claims are accompanied by citations in the format【source†lines】.

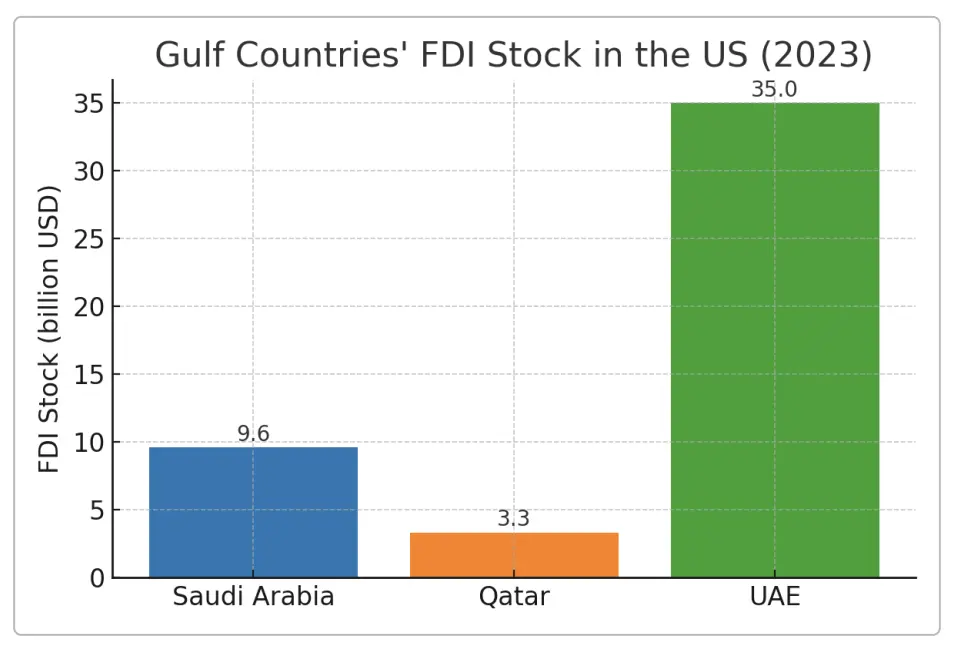

Overview of U.S.–Gulf Economic Ties: The United States has long-standing economic relationships with Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the UAE, traditionally centered on the energy trade and defense sales. For decades, the U.S. imported Gulf oil and gas while exporting military equipment and services. In recent years, however, the relationship has evolved into a more multifaceted partnership including bilateral investment flows. U.S. companies have pursued opportunities in Gulf markets (from participating in Gulf infrastructure megaprojects to establishing tech and consulting operations), and Gulf sovereign wealth funds have increasingly looked to deploy capital in Western markets, especially in the U.S., to earn stable returns and acquire technology and expertise. By 2023, bilateral trade and investment figures reflected this deepening engagement. The U.S. Department of Commerce reported that in 2023 U.S. foreign direct investment stock in Saudi Arabia was $11.3 billion, in Qatar $2.5 billion, and in the UAE $16.1 billion. Conversely, Gulf countries’ cumulative FDI in the United States, while smaller, has been growing: Saudi Arabia’s FDI stock in the U.S. reached about $9.6 billion in 2023, Qatar’s about $3.3 billion, and the UAE’s about $35 billion. (These figures exclude portfolio investments and short-term capital flows, focusing only on direct investments in businesses and projects.)

This pattern – a relative imbalance in FDI, with U.S. investments in the Gulf often exceeding Gulf FDI in the U.S. – began to shift as Gulf states amassed greater sovereign wealth and proactively sought investment opportunities abroad. High oil and gas prices in the 2021–2024 period, combined with Gulf governments’ economic diversification agendas, boosted the capacity and appetite of Gulf sovereign funds to invest overseas. The stage was thus set for the surge of Gulf-to-U.S. investments observed in 2023–2025. Notably, the period saw top-level diplomatic engagement to facilitate investment: high-profile meetings and strategic dialogues were used as platforms to announce ambitious economic initiatives. For example, the U.S.–Qatar Strategic Dialogue (concluding in early 2023) reinforced commitments to remove obstacles to bilateral investment, and U.S. diplomatic engagements with Saudi and Emirati leadership in 2025 explicitly prioritized investment cooperation. By May 2025, these efforts culminated in what officials described as a “new golden era” of U.S.–Gulf economic partnership, characterized by Gulf states pledging unprecedented capital to American projects and enterprises.

Overview of Aggregate Investments (2023–May 2025)

Rising Investment Volumes: From January 2023 through May 2025, Gulf investments into the U.S. accelerated markedly. In aggregate, dozens of deals were struck across sectors ranging from energy to tech, with headline-grabbing totals attached to publicly announced agreements. By mid-2025, the announced Gulf commitments to U.S. investments reached roughly $3.2 trillion when combining the multi-year frameworks unveiled by Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the UAE. This figure includes long-term investment programs (spanning up to a decade) and major one-time transactions. It is crucial to note that such sums incorporate broad economic agreements and memoranda – including anticipated future outlays and procurement – not only immediate FDI. In contrast, actualized FDI flows from the Gulf during 2023–2024 were much smaller, on the order of tens of billions of dollars. For perspective, new Gulf FDI flows into the U.S. in 2023 were likely in the single-digit billions (building on the aforementioned stock of ~$48 billion combined for KSA, UAE, Qatar), whereas the committed (future) investments announced in early-to-mid 2025 are over two orders of magnitude larger. This disparity underscores a theme of this period: Gulf leaders signaling extraordinary future investment intentions, even as on-the-ground capital deployment ramps up more gradually.

Committed vs. Actualized Investments: A distinguishing feature of 2023–2025 is the contrast between committed and realized investments. All three countries made splashy announcements of large-scale investment programs: for example, the UAE’s $1.4 trillion framework aims to “substantially increase” its investments in the U.S. economy over the next decade, and Saudi Arabia intends to invest up to $600 billion in the U.S. over four years. Qatar likewise agreed to an economic exchange worth $1.2 trillion during a May 2025 summit. These commitments are forward-looking and often encompass broad areas of cooperation (including procurement of U.S. goods, co-investment funds, and greenfield projects). In terms of actual deals executed in 2023–early 2025, the tally is more modest but still historically high. Key deals that were signed or put in motion in this period include:

Defense and Aerospace: Saudi Arabia and Qatar each signed huge defense procurement contracts with U.S. companies (e.g. Qatar’s $1 billion counter-drone systems from Raytheon and $2 billion MQ-9B drone purchase from General Atomics; Saudi Arabia’s nearly $142 billion in various U.S. defense procurements, the largest U.S.-Saudi arms package ever). Qatar Airways placed a $96 billion order for Boeing 787 and 777X aircraft with GE engines – Boeing’s largest widebody aircraft order in history.

Artificial Intelligence and Tech: Gulf investments targeted U.S. tech innovation through both direct equity stakes and joint initiatives. Notably, Saudi Arabia’s PIF (Public Investment Fund) established a new AI-focused investment program and, alongside tech partners, announced $80 billion to be invested in “cutting-edge transformative technologies” in the U.S. and Saudi Arabia. Qatar’s QIA participated in major Silicon Valley funding rounds (for example, it joined a $6 billion funding round for Elon Musk’s AI startup “xAI” in 2024) and set up a joint venture in quantum computing with U.S. firm Quantinuum, committing $1 billion to develop quantum technologies and workforce skills in both countries. The UAE, aiming to be a global AI leader, unveiled plans to invest heavily in AI infrastructure and semiconductors in the U.S. as part of its $1.4T framework.

Clean Energy and Infrastructure: Gulf capital flowed into U.S. energy projects, especially LNG and renewables, reflecting both commercial opportunity and energy security ties. QatarEnergy (via a joint venture with ExxonMobil) continued constructing the Golden Pass LNG export terminal in Texas – a $10+ billion project that will bolster U.S. LNG export capacity (completion now expected by 2025–26). From the UAE side, ADNOC’s new investment arm (XRG) committed funding to NextDecade’s LNG export facility in Texas, and UAE’s ADQ teamed with U.S. investors on a $25 billion initiative in U.S. energy infrastructure and data centers. Additionally, Emirates Global Aluminium (EGA) announced it will invest in building the first new aluminum smelter in the U.S. in 35 years – a project that would nearly double U.S. primary aluminum production capacity. In green energy, Saudi and Emirati funds showed interest in U.S. clean tech and EV sectors (Saudi’s PIF, for instance, remains a major backer of U.S.-based Lucid Motors and is exploring other EV and battery ventures).

Real Estate and Tourism: Gulf investors continued to acquire high-profile U.S. real estate and hospitality assets. Qatari Diar (Qatar’s real estate arm) and other Qatari investors have put money into projects like the $700 million renovation of the Manhattan West development and luxury hotels, contributing to Qatar’s focus on hotels and tourism in its U.S. portfolio. The UAE and Saudi private investors have also been active in real estate; for example, Saudi and Emirati funds were reported as key financiers in large U.S. property deals and real estate investment trusts, though specific 2023–24 deal values are not all public.

Finance and Investment Funds: A significant mode of Gulf investment is through partnerships with U.S. asset managers and the creation of co-investment funds. Saudi Arabia’s PIF struck multi-billion-dollar investment deals with major U.S. investment firms (e.g. partnering with BlackRock, Franklin Templeton, and Neuberger Berman to channel U.S. investments into Saudi and vice-versa). Qatar’s QIA opened a New York office and has been allocating billions into U.S. private equity and venture capital funds, including a $1+ billion allocation to a new fund-of-funds program to support startups (announced in early 2024). The UAE’s Mubadala and ADIA continued making substantial portfolio investments in U.S. equities, tech companies, and real estate funds – Mubadala, for instance, is a cornerstone investor in some U.S. venture funds and co-investments in life sciences.

In aggregate, these deals represent a sharp uptick compared to prior periods. By comparison, in the late 2010s, Gulf investments in the U.S. were significant but tended to be isolated large deals (e.g. Qatar investing ~$5 billion in U.S. real estate or Saudi’s PIF investing $45 billion in SoftBank’s Vision Fund, much of which went to U.S. tech startups). The 2023–2025 period, however, is characterized by a more comprehensive investment drive, with Gulf capital targeting a broader swath of the U.S. economy – from heavy industry to cutting-edge tech – and doing so in a coordinated fashion aligned with diplomatic initiatives. A quick look at previous periods underscores the change: for example, Qatar had pledged $45 billion for U.S. investments in 2015 and likely met that goal by the early 2020s, but now has agreed to a framework potentially several times larger. The UAE’s FDI stock in the U.S. roughly doubled from about $17 billion in 2017 to $35 billion in 2023, and now Abu Dhabi alone is eyeing an order-of-magnitude leap via the $1.4 trillion plan. Saudi Arabia’s direct investment in the U.S., which was minimal a decade ago, is now poised to surge if the announced deals are implemented (Saudi FDI in the U.S. only reached ~$1–2 billion annually in the late 2010s; the new Vision 2030-driven strategy has the Kingdom targeting hundreds of billions in U.S. projects). In summary, the trajectory is sharply upward, with 2025 representing a potential inflection point turning years of incremental growth into a phase of exponential commitments.

Major investment commitments announced by Gulf states in early 2025 (in billion USD). These headline figures include multi-year frameworks and anticipated deals. The committed values far exceed the current invested stock, indicating the Gulf’s aspirations for the next decade.

Country-Specific Deep Dives

Saudi Arabia (KSA) Investments in the U.S. (2023–May 2025)

Investment Figures & Timeline: Saudi Arabia’s investment in the United States accelerated significantly through 2023–25, driven by the Kingdom’s sovereign wealth powerhouse – the Public Investment Fund (PIF) – and high-profile bilateral initiatives. As of 2023, the total stock of Saudi FDI in the U.S. was relatively modest at $9.6 billion (focused mainly in transportation, real estate, automotive, and financial services). However, 2024–2025 saw the announcement of dramatically larger commitments. In early 2025, Saudi Arabia pledged to ramp up investments in the U.S. to at least $600 billion over four years. This pledge was unveiled as part of a historic package of U.S.–Saudi agreements announced during President Trump’s visit to the Kingdom in 2025. A fact sheet released in May 2025 detailed that over the preceding months, a series of deals “quickly built to more than $600 billion – the largest set of commercial agreements on record” between the two countries. The timeline of key developments is as follows:

2023: Steady investment activity via PIF and private Saudi investors. PIF’s U.S. equities portfolio fluctuated with market conditions – after peaking near $60 billion in 2021, it was about $26–27 billion by end of 2024 (due to valuation changes, e.g. Lucid Motors stock drop). In 2023, Saudi direct investment flows targeted sectors like EV manufacturing (continued funding for Lucid’s U.S. operations), gaming and tech (PIF raised stakes in U.S. gaming companies and invested in tech funds), and real estate (some high-net-worth Saudis reportedly purchased luxury properties in states like New York and Florida). Notably, Saudi Aramco, the state oil giant, also expanded its U.S. footprint through its subsidiaries – for instance, Aramco Americas launched new research centers and considered downstream investments, while Aramco’s trading arm increased activities in U.S. energy markets. These moves were preparatory to larger strategic investments.

2024: Intensified strategic dialogues and minor setbacks. Early 2024 saw diplomatic talks laying groundwork for bigger deals, with Saudi officials expressing interest in U.S. infrastructure and advanced industries. However, PIF simultaneously recalibrated its investment strategy – there were reports that PIF was slowing some spending domestically to focus on high-impact projects and international investments. In mid-2024, a notable incident was Saudi interests’ involvement in global finance: Saudi National Bank (part-owned by PIF) briefly became a top shareholder of Credit Suisse, though this European bank investment turned sour when Credit Suisse collapsed in 2023 (highlighting risks of overseas investments, though not directly a U.S. case). By late 2024, anticipation grew that Saudi Arabia would leverage its strong financial position (buoyed by oil prices) to make a splash in the U.S. – indeed, President Trump publicly urged Saudi Arabia in January 2025 to invest $1 trillion in the U.S. economy, signaling that a major deal was in the works.

Early 2025: Grand investment accords. In April–May 2025, Saudi-U.S. negotiations yielded a comprehensive investment agreement package. When President Trump visited Riyadh (his first foreign trip of the new term, per reports), a range of deals were signed totaling ~$600 billion. These included Saudi investments in U.S. ventures and U.S. companies’ participation in Saudi megaprojects, creating a two-way capital flow. For example, Saudi’s DataVolt company announced a $20 billion investment in U.S. data centers and energy infrastructure to bolster cloud computing and AI capabilities. In technology, a joint statement listed U.S. tech giants (Google, Oracle, Salesforce, AMD, Uber) alongside DataVolt committing $80 billion towards “transformative technologies” in both the U.S. and Saudi Arabia – a sign of deep tech collaboration. Several sector-specific Saudi investment funds were also launched with a U.S. focus: a $5 billion Energy Investment Fund, $5 billion New Era Aerospace & Defense Technology Fund, and a $4 billion Global Sports fund, all of which will deploy substantial capital into American industries (from clean energy projects to defense startups to sports and entertainment ventures). Additionally, Saudi entities placed orders for U.S. products that have investment-like impact: e.g. a Saudi airline leasing firm (AviLease) ordered Boeing jets worth $4.8B, and Saudi utility projects ordered $14.2B in GE Vernova gas turbines and energy solutions – these deals are counted in the $600B package and will stimulate U.S. manufacturing. Saudi healthcare investment was also noted, with a plan to invest $5.8B in U.S. medical manufacturing (including a new IV solutions plant in Michigan).

Key Sectors and Projects: Saudi investments have targeted a broad array of sectors, with technology, energy, defense, and entertainment/sports among the priorities:

Technology & AI: Saudi Arabia has signaled that leadership in AI and tech is a strategic goal. PIF has been investing in U.S. tech firms that can support Saudi’s domestic “knowledge economy” ambitions. This includes stakes in Silicon Valley companies (PIF owns shares in companies like Uber, Lucid, semiconductor firms, and gaming companies) and funding of U.S. tech startups. The new $20B DataVolt initiative to build U.S. data centers is intended to not only earn profits but also learn best practices for Saudi’s growing cloud/AI sector. Moreover, collaborations like Saudi’s JV with Foxconn (to create the Ceer EV brand) involve U.S. tech indirectly (since Foxconn and others operate in the U.S. as well). In AI research, Saudi Arabia’s NEOM project and KAUST have partnerships with U.S. AI labs, and as part of the 2025 deals, it’s likely that U.S. AI companies will receive Saudi investment under the $80B tech commitment.

Defense & Aerospace: This is both a traditional and a newly evolving sector for investment. Traditionally, Saudi Arabia has been a purchaser of U.S. defense systems (as seen with the $142B arms deal covering aircraft, missiles, etc.). What’s new is Saudi’s interest in investing in defense tech – e.g., the New Era Defense Technology Fund ($5B) will likely invest in American defense startups or funds to bring cutting-edge military tech to Saudi while supporting the U.S. industrial base. Also, Saudi industry is co-developing defense projects with U.S. firms (for instance, there are talks of joint production of components in Saudi Arabia for U.S. defense primes, which blurs the line between inward and outward investment). Aerospace falls in this category too: beyond military, Saudi’s civil aviation expansion (new airlines, airports) involves big orders to Boeing and partnerships (e.g., Boeing’s deal to potentially set up some assembly in Saudi) – again, these are commercial sales but entwined with investment pledges. The $5B aerospace fund suggests Saudi capital will back U.S. aerospace ventures (perhaps space startups or urban air mobility companies).

Energy (Oil, Gas, Clean Energy): Saudi Arabia’s investments in U.S. energy have been somewhat cautious historically (Aramco owns the largest refinery in the U.S. – Motiva in Texas – which it gained full control of in 2017, and has invested in U.S. downstream assets). In the 2023–25 window, Saudi’s focus is on clean energy and new energy tech in the U.S.: for example, the joint $5B Energy Investment Fund aims to invest in areas like renewables, carbon capture, and perhaps U.S. LNG infrastructure. Additionally, Saudi-owned companies are partnering in U.S. clean energy projects (one public example is ACWA Power discussing U.S. renewable investments). Oil and gas ties remain strong: Aramco’s venture arm in 2023 took stakes in U.S. energy tech startups (like companies developing next-gen fuels, AI for oilfields, etc.). It’s also worth noting that as the U.S. became a major oil producer, Saudi sovereign funds started to look at U.S. shale infrastructure in a financial investment sense (though no major acquisition has been confirmed, interest was reported in pipelines and LNG terminals).

Infrastructure & Real Estate: Saudi Arabia’s Ministry of Investment and PIF have promoted co-investment in infrastructure. As part of the 2025 agreements, American engineering firms (Jacobs, AECOM, Parsons) got contracts for Saudi projects, effectively meaning Saudi funds are paying U.S. companies, which then may invest in U.S. operations. Domestically in the U.S., PIF had explored investing in American infrastructure funds (for instance, there were discussions about Saudi funding for U.S. infrastructure initiatives during the previous U.S. administration). In real estate, aside from a few high-profile deals (e.g. a Saudi investment group buying a stake in NYC’s Plaza Hotel in 2018, or partnering in some U.S. commercial property deals), Saudi investments have been less visible than Qatar/UAE’s. But PIF’s strategy includes real estate tech and logistics – PIF took stakes in U.S. logistics real estate (warehouses, etc.) and in 2023 explored investing in digital infrastructure (data center real estate, etc.). We can expect more in this vein under the data center initiative.

Sports & Entertainment: An intriguing sector is sports/entertainment, highlighted by the $4B sports fund that will invest globally (including in U.S. sports ventures). Already, Saudi PIF made waves by investing in LIV Golf, which effectively merged with the U.S. PGA Tour in 2023, meaning Saudi capital now underpins a major part of U.S. professional golf. Saudi investors have also bought stakes in esports organizations and considered investments in U.S. media companies. These are both financial investments and tools of soft power. The sports fund could potentially look at everything from U.S. sports franchises to media rights companies. Entertainment-wise, Saudi’s NEOM Media Village has partnerships with U.S. Hollywood studios, and Saudi investors have financed some Hollywood films and startups. These cross-border cultural investments often fly under radar but are growing.

Investment Vehicles: The primary vehicle for Saudi investment in the U.S. is the Public Investment Fund (PIF). Chaired by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, PIF has grown to manage about $930 billion in assets as of 2024, making it one of the world’s largest sovereign funds. PIF is pursuing a dual mandate: invest abroad for financial returns and strategic assets, and invest at home to develop new industries. In the U.S., PIF operates through direct investments and through fund partnerships. It files quarterly 13F reports for its U.S. equity holdings (which have included blue chips like Citigroup, Facebook, Disney in the past). PIF’s U.S. equity portfolio was around 59 companies at end-2024, indicating a significant footprint in corporate America. Beyond PIF, other Saudi entities include: Saudi Aramco (with its investment arms and JV partnerships), which although mainly focused on energy, also can make tech investments (for example Aramco’s VC fund invested in a U.S. EV battery startup in 2023); Saudi Arabian Military Industries (SAMI), which might invest in or form joint ventures with U.S. defense firms as part of offset agreements; and private investment firms like Kingdom Holding (Prince Alwaleed’s firm, known for big stakes in Citigroup, Twitter, Lyft, etc., though in 2022 PIF acquired a large share of Kingdom Holding, aligning its activities more with state strategy). Also, Saudi banks and insurance companies have allocations to U.S. markets, but these are portfolio investments not FDI. When it comes to deploying the huge $600B commitment, special-purpose vehicles and funds are likely to be set up – for example, a joint U.S.-Saudi fund for infrastructure or an innovation fund (the fact sheet hints at “sector-specific funds” which presumably will be managed in partnership with U.S. financial institutions).

Flagship Projects & U.S. Partners: Saudi Arabia’s deep dive into the U.S. economy involves several flagship projects and notable partnerships:

In manufacturing, a headline project is the planned EV assembly plant by Lucid Motors in Arizona, which PIF’s majority ownership made possible. This facility (under construction as of 2023) is creating thousands of U.S. jobs, illustrating how Saudi investment can bolster U.S. industry (Lucid’s investment is ~$700 million in its Arizona factory, supported by Saudi capital).

In energy infrastructure, Saudi Aramco’s JV in the Port Arthur refinery expansion (Motiva’s planned $6.6B petrochemical expansion) stands out – a project shelved earlier but possibly revived by Saudi’s interest in downstream U.S. investments.

The DataVolt initiative (mentioned earlier) is effectively a project to build cutting-edge data centers in the U.S. – presumably in partnership with U.S. cloud providers (e.g., Google Cloud or Oracle Cloud). This could make DataVolt (a Saudi company) an important player in U.S. cloud infrastructure, likely in joint ventures.

Defense partnerships include potential joint production of defense systems. Boeing and Lockheed Martin have existing industrial partnerships in Saudi; under the new agreements, some Saudi investment might flow into U.S. facilities (e.g. co-development of fighter jet parts or aerospace R&D centers in the U.S. funded by Saudi). Raytheon’s drone defense sale to Qatar in 2025, and possibly similar systems to Saudi, could come with Saudi financing of R&D for next-gen systems in the U.S.

Bilateral Agreements: The U.S. and Saudi Arabia have institutionalized some of this cooperation via agreements like the U.S.-Saudi Investment Framework (established in 2017 and revitalized recently) and MOUs on energy and infrastructure. In 2023–24, the two governments worked on frameworks to facilitate Saudi sovereign investment in American infrastructure (the Saudi Ministry of Investment signed MOUs with U.S. Department of Commerce, for example, to identify opportunities in sectors like semiconductors and 5G). In 2025, alongside the big deals, the countries likely updated their Trade and Investment Council Agreement to reflect the expanded partnership, emphasizing knowledge transfer, localizing manufacturing (some U.S. companies producing in Saudi and Saudi capital funding production in the U.S.). One explicit piece was an agreement to deepen cooperation in critical minerals and green energy, ensuring Saudi investment in U.S. mining or battery supply chains may occur (as the U.S. seeks reliable sources and Saudi seeks to learn the industry).

Overall, Saudi investments in the U.S. from 2023 to May 2025 moved from a relatively small-scale to a potentially game-changing scale. If even a fraction of the $600B commitment is realized, it would mark an unprecedented Saudi economic engagement with the U.S. The mix of sectors – from Silicon Valley tech to Midwestern manufacturing – shows Saudi Arabia positioning itself not just as an oil supplier or arms buyer, but as a broad investor in America’s economic future.

Qatar Investments in the U.S. (2023–May 2025)

Investment Figures & Timeline: Qatar’s financial relationship with the U.S. is underpinned by the Qatar Investment Authority (QIA), a sovereign wealth fund managing over $500 billion in assets, alongside strategic state-owned companies like QatarEnergy. As of 2023, Qatar’s FDI stock in the United States was around $3.3 billion – smaller than Saudi’s or UAE’s, partly due to Qatar’s population and economy being smaller, but also because Qatar historically invested heavily in Europe and Asia. However, Qatar has made substantial U.S. portfolio investments and long-term commitments that don’t fully reflect in FDI stock. Notably, in 2015 Qatar pledged to invest $45 billion in the U.S. within 5 years, a goal it has likely met or exceeded by the early 2020s when counting all forms of investment (including real estate and fund investments). The period 2023–2025 saw Qatar renew and escalate its U.S. investment drive:

2023: Qatar continued steady investments, particularly via QIA’s participation in high-profile deals. For example, in January 2023, QIA doubled its stake in Credit Suisse (though that was a European bank, it highlighted Qatar’s willingness to invest during market distress). In the U.S., QIA focused on tech and venture investments throughout 2023. It joined funding rounds for U.S. startups such as Instabase (AI-powered data platform) and Beta Technologies (electric aviation startup), leading a $318 million Series C for the Vermont-based company in 2023. Qatar also invested in U.S. funds aimed at supporting minority-owned businesses (e.g. QIA put money into Project Black, a private equity fund by Ariel Alternatives in 2023, to spur minority-owned enterprises). These show Qatar’s nuanced strategy of combining financial return with soft diplomacy (aligning with U.S. social initiatives). Meanwhile, QatarEnergy pursued a major U.S. project: the Golden Pass LNG terminal in Texas, a joint venture with ExxonMobil. Construction was in full swing in 2023, representing a Qatari capital commitment of around $5+ billion (QatarEnergy holds 70% of the $10 billion project)goldenpasslng.com. This is a direct investment in U.S. energy export capacity and is central to Qatar’s timeline, as it expands Qatar’s global LNG reach by using U.S. soil.

2024: A year of strategic alignment and new leadership in QIA. Early 2024 saw Qatar’s Prime Minister (who is also QIA Chairman) celebrating one year of QIA’s new Fund-of-Funds program, to which QIA committed $1 billion for investments in tech VC funds (announced at the Web Summit Qatar) – a portion of that likely channels into U.S. tech startups via venture funds. In January 2025 (technically on the cusp of 2024/25), QIA’s head of technology made headlines at Davos, expressing optimism that the new U.S. administration would spur a “boom in U.S. technology deals” – QIA was positioning to take advantage of a more pro-investment climate. Also in 2024, Qatar re-engaged with Washington in formal dialogues: the 5th U.S.-Qatar Strategic Dialogue, concluding in March 2023, had already addressed barriers to investment, and ongoing talks in 2024 likely paved the way for bigger announcements. A significant change was QIA’s leadership shuffle: a new CEO (HE Mohammed Al-Sowaidi) was appointed in late 2023, with a mandate to be more aggressive in deploying Qatar’s surging LNG wealth into global markets. Under his leadership, by late 2024 QIA increased its U.S. focus – for instance, reports emerged of QIA considering stake buys in major U.S. tech infrastructure (such as data center companies) and partnering with U.S. asset managers for large transactions.

May 2025: Major deals and commitments. The highlight was President Trump’s visit to Doha in May 2025, during which Qatar and the U.S. signed an economic agreement valued at $1.2 trillion. This headline figure encapsulates anticipated investments and trade over the coming years. As part of this, over $243.5 billion in specific deals were detailed. Key components of the Qatar-U.S. deals included: Qatar Airways’ aforementioned $96 billion purchase of Boeing jets (a huge boost for Boeing and U.S. aerospace jobs); a deepening of QatarEnergy’s partnerships – for example, McDermott International (a U.S. engineering firm) is executing $8.5B worth of LNG infrastructure projects for Qatar, thereby funneling expertise and supporting U.S. jobs in engineering; Parsons, a U.S. engineering company, had won 30 project contracts in Qatar totaling up to $97B (covering infrastructure for the World Cup and beyond), which indirectly benefits U.S. industry via exports of services. On the investment side, a standout was Quantinuum’s joint venture with Qatar’s Al Rabban Capital, where Qatar will invest up to $1 billion in quantum computing tech in the U.S., linking Qatar to a cutting-edge U.S. tech field. Additionally, there were defense procurement deals: Qatar inked a $1B agreement with Raytheon for advanced counter-drone systems (making Qatar the first international buyer of that U.S. system) and a ~$2B deal for General Atomics MQ-9B Reaper drones – these are Qatari purchases, but significant because they lock in long-term security cooperation and production work in the U.S. There was also a signed Statement of Intent to explore $38B more in defense investments (including upgrading the U.S. Al-Udeid Air Base infrastructure that Qatar helps fund, and future air defense systems). In summary, May 2025 crystallized Qatar’s investment timeline with both immediate big-ticket purchases and longer-term pledges to invest more in sectors like quantum tech, aerospace, and energy.

Key Sectors and Projects: Qatar’s U.S. investment portfolio spans several key sectors, often aligning with Qatar’s own economic strengths (LNG, aviation) and diversification goals (tech, real estate):

Energy and LNG: Qatar’s prominence in LNG has directly translated into U.S. investments. The Golden Pass LNG project in Texas is a flagship – when completed around 2025/26, it will make Qatar a supplier of U.S. LNG exports, entrenching a long-term Qatar-U.S. energy partnership. QatarEnergy’s investment goes beyond just an ownership stake; they are also sharing know-how and possibly will use U.S.-made equipment (Caterpillar turbines, etc., boosting U.S. exports). Additionally, Qatar (through power companies or Nebras Power) has shown interest in U.S. power generation assets and renewables. In 2023, for example, Nebras Power invested in a U.S. solar energy portfolio. So clean energy is on the radar – QIA joined a $300M funding in TechMet (a U.S.-headquartered critical minerals company) in 2024, which secures supply chains for rare minerals needed in clean tech. This aligns with Qatar’s aim to be involved in green technology while supporting U.S. efforts to develop battery metals responsibly.

Technology and Innovation: QIA has been explicitly ramping up tech investments in the U.S. It opened a Silicon Valley office a few years back to scout opportunities. Key focus areas include AI, fintech, biotech, and enterprise software. Qatar’s stake in Twitter (now X) – QIA was part of Elon Musk’s takeover consortium in 2022 – is a notable tech investment. Building on that, QIA’s participation in Musk’s new venture xAI and possibly others suggests Qatar positions itself as a partner for major U.S. tech entrepreneurs. The quantum computing JV (Quantinuum) is a prime example of strategic tech investment: it not only promises financial return if quantum tech succeeds but also gives Qatar a seat at the table in an emerging strategic industry alongside U.S. and UK partners (Quantinuum is a U.S.-UK joint firm). Artificial Intelligence startups and funds are another area – QIA has put money into AI-focused venture funds run by U.S. firms (e.g. $QIA’s commitment to a $10B Global Tech Fund led by a U.S. manager, reported in 2024). By emphasizing tech, Qatar aims to future-proof its wealth (earning from tech booms) and bring knowledge back to its own nascent tech sector (e.g. via partnerships between U.S. companies and Qatar’s innovation centers like Qatar Science & Tech Park).

Real Estate and Hospitality: Qatar is well-known for its trophy real estate investments, especially in Europe (e.g. London’s Shard, Harrods) and the U.S. as well. Through QIA and its real estate arm Qatari Diar, Qatar has invested in projects like CityCenterDC in Washington D.C. (a large mixed-use development completed with Qatari funding) and has acquired stakes in iconic properties (the Plaza Hotel NYC was Qatari-owned until 2018; QIA also bought a stake in Empire State Realty Trust in 2016). Between 2023–25, Qatar continued this trend: one example, QIA in 2023 increased its stake in Brookfield’s U.S. real estate projects, and joined a consortium acquiring a portfolio of student housing in the U.S. In the hospitality sector, Katara Hospitality (Qatar’s hotel investment arm) was reportedly exploring investments in U.S. hotel chains or properties post-COVID. The fact sheet explicitly notes Qatar’s greenfield investment focus in 2023 included hotels and tourism – presumably Qatar is backing developments of resorts or urban hotels in the U.S., leveraging its expertise as a major global hotel owner.

Financial Services: Qatari investors have been involved in U.S. financial institutions. QIA owns a minor stake in UBS via Credit Suisse and previously in Barclays – not directly U.S., but QIA also held shares in U.S. companies like NYSE (stock exchange) through a consortium. In 2023, QIA put $200 million into a SPAC (special purpose acquisition company) partnering with tech entrepreneurs in the U.S. Additionally, Qatar’s large holdings of U.S. Treasury bonds (over $7B in U.S. treasuries as per U.S. Treasury data) make it a key financial stakeholder. Going forward, Qatar is exploring establishing a fintech hub with U.S. cooperation – part of the strategic dialogue outcomes was cooperation on financial innovation, meaning Qatari funds may invest in U.S. fintech startups and, conversely, U.S. fintech firms may set up in Doha with support.

Defense and Security Tech: While Qatar historically relied on buying defense equipment, it is now also investing in defense tech development. The Raytheon and General Atomics deals in 2025 might include arrangements for local assembly or R&D that Qatar finances. Moreover, Qatar has invested in security-related tech startups in the U.S. (for example, through its venture arm, it funded a U.S. drone tech company in 2022). This sector is smaller for Qatar than for Saudi/UAE, but as it hosts the Al-Udeid Air Base, Qatar has an interest in the U.S. defense industry’s future – it even offered to finance U.S. expansions at Al-Udeid (hence the $38B potential investments for defense in the MoU could include Qatar funding construction and tech upgrades that benefit U.S. forces).

Investment Vehicles: Qatar’s main investment conduit is the Qatar Investment Authority (QIA). QIA was established in 2005 and has grown to be one of the world’s largest sovereign funds, with an estimated $450–$510 billion in assets by 2025. QIA invests across asset classes: public equities, private equity, real estate, infrastructure, and direct company stakes. It often co-invests with renowned U.S. investment firms (e.g. with Brookfield Asset Management in real estate deals, or with BlackRock in infrastructure funds). QIA’s New York office (opened 2015) facilitates these U.S. deals. Besides QIA, Qatar has other vehicles: Qatari Diar (real estate development, behind CityCenterDC, etc.), Qatar Sports Investments (QSI) which has focused on sports teams in Europe (PSG) but could in theory invest in U.S. sports or entertainment ventures, and Qatar Foundation (non-profit, but through its endowment it invests in education and tech initiatives and has funded branch campuses of U.S. universities in Education City, Doha – effectively an investment in intellectual capital exchange). Also, Qatar Airways itself acts as an investor when it buys fleets of U.S. aircraft; it has a stake in CargoLux (European cargo airline) and might consider stakes in U.S. carriers if allowed (not currently, due to foreign ownership limits). Private Qatari investors (often members of the royal family) have also invested in the U.S. – for instance, former PM Hamad bin Jassim (HBJ) has a significant investment portfolio globally. But these are smaller scale compared to QIA. Notably, QIA often prefers partnerships – e.g., the $10 billion QIA–Citigroup infrastructure fund launched in 2017 focused partly on North America. In 2025, as part of the new commitments, one could expect QIA to set up dedicated funds for U.S. investments (similar to how UAE’s Mubadala did in the past).

Flagship Projects & U.S. Partners: Qatar’s engagement with the U.S. has produced several flagship collaborative projects:

The Golden Pass LNG export terminal in Sabine Pass, Texas is emblematic – a joint venture of QatarEnergy (70%) and ExxonMobil (30%). It’s slated to export up to 18 million tons of LNG per year, making it a significant piece of U.S. energy infrastructure funded largely by Qatar. This project employs thousands of American workers in construction and will generate ongoing export revenue (benefiting both countries).

Boeing-Qatar Airways partnership: The mega-order of 100+ aircraft (announced 2022, expanded by 2025) cements Boeing’s relationship with Qatar. It’s a flagship in that it secures Boeing’s production line for years and deepens Qatar’s reliance on U.S. tech for its aviation needs. GE Aerospace engines in that deal also mean a multi-decade maintenance and support relationship.

U.S. University Campuses in Qatar: While reverse (U.S. investment in Qatar), it’s worth noting as partnership – six American universities (Cornell, Carnegie Mellon, Georgetown, etc.) have branches in Doha funded by Qatar Foundation. This entanglement means knowledge flows both ways, and U.S. institutions benefit from Qatari funding (over $6.25B granted to U.S. universities by Qatar since 2012). It’s an unconventional “investment” by Qatar into U.S. education, and has stirred debate about influence, which we’ll cover in risks.

Bilateral Agreements: The U.S. and Qatar have a robust framework via the annual Strategic Dialogue. Outcomes include MOUs on energy cooperation (e.g., a 2021 MOU on energy that likely aided Golden Pass’s progress), and an MOU on commercial cooperation signed in 2021 focusing on fintech and supply chains. In 2022, Qatar was designated a Major Non-NATO Ally by the U.S., which, beyond military meaning, signaled greater economic and tech collaboration. In 2025, the new agreements likely updated the U.S.-Qatar Economic Partnership to target emerging sectors – for example, the fact sheet notes Qatar’s National Vision 2030 creates opportunities for U.S. business in health, ICT, etc., implying reciprocal Qatari investment in those U.S. sectors to glean expertise.

In sum, Qatar’s investments in the U.S. during 2023–May 2025, while not as gargantuan in headline number as Saudi’s or UAE’s, are highly strategic and targeted. Qatar leverages its strengths (massive LNG revenue and a nimble sovereign fund) to invest in areas that yield not just profits but also influence and knowledge – from owning prime real estate and supporting key industries (aircraft, energy) to placing itself at the forefront of emerging tech partnerships with the U.S. The result is a quietly significant presence: Qatar may have only a few billions in recorded FDI, but its overall economic imprint in the U.S. – through purchases, investments, and financing – is far larger (one study estimated $33.4 billion in QIA business deals in the U.S. since 2012). The 2025 deals mark an elevation of Qatar as a major economic partner to the U.S., beyond its outsized geopolitical role (hosting U.S. troops, mediating conflicts).

United Arab Emirates (UAE) Investments in the U.S. (2023–May 2025)

Investment Figures & Timeline: The UAE has long been the Gulf’s leader in outbound investment, and this extends to its investments in the United States. By 2023, the UAE’s cumulative FDI stock in the U.S. was about $35 billion – greater than the combined Saudi and Qatari FDI in the U.S. This reflects decades of significant UAE investment, particularly via Abu Dhabi’s sovereign wealth funds (ADIA and Mubadala) in sectors like real estate, infrastructure, and tech. U.S. Commerce data indicates those UAE investments have been concentrated in financial services, transport, food & beverage, aerospace, and business services. Meanwhile, U.S. FDI in the UAE was around $16.1B in 2023, illustrating robust two-way ties. The timeline for 2023–25 shows the UAE building on this base with bold new commitments:

2023: The UAE’s investment pace in the U.S. was steady, highlighted by some major fund allocations. Mubadala – Abu Dhabi’s strategic investment firm (~$330B AUM) – increased its exposure to U.S. tech: it invested in ventures like the G42-U.S. tech fund (G42, an Abu Dhabi AI company, set up a $10B fund with Silicon Valley’s Silver Lake; Mubadala is backing it). Also in 2023, ADIA (Abu Dhabi Investment Authority), one of the world’s largest SWFs, reportedly put more capital into U.S. alternative assets (from logistics real estate to private equity). ADIA doesn’t disclose deal-by-deal info, but market analysts noted ADIA was targeting U.S. infrastructure projects (e.g., toll roads, data centers) as valuations became attractive. On a smaller scale, Dubai’s enterprises made moves: Emaar (developer) explored property development in U.S. cities, and Emirates Airline invested in U.S. tourism promotion via partnerships. Politically, late 2023 saw groundwork for a larger partnership – at a meeting in December, U.S. and UAE officials discussed elevating economic ties, potentially foreshadowing the big announcement to come.

Early 2024: The UAE continued diversifying its U.S. portfolio. In tech, Chimera Investments (Abu Dhabi) and other UAE venture vehicles took stakes in U.S. fintech and health-tech startups. By mid-2024, anticipation grew that the UAE would announce a major investment initiative as part of improving ties with the new U.S. administration. Indeed, in September 2024, UAE President Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed (MBZ) visited the White House (meeting then-President Biden) – the first ever UAE head-of-state official visit – and they discussed deepening cooperation in AI, investments, and space. While no trillion-dollar figure was mentioned then publicly, it set the stage for a comprehensive deal. Additionally, in 2024 the UAE and U.S. collaborated on the I2U2 initiative (with Israel and India) which included plans for UAE to invest in green projects (like solar farms in India with U.S. and Israeli tech), showing UAE’s role as a capital exporter in U.S.-led partnerships.

March 2025: The breakthrough came when the UAE delegation, led by National Security Adviser Sheikh Tahnoon bin Zayed (who also chairs key sovereign funds ADQ and FAB), met President Trump in Washington. On March 21, 2025, the White House announced the UAE’s commitment to a 10-year, $1.4 trillion investment framework in the U.S.. This jaw-dropping figure, by far the largest ever single-country investment pledge to the U.S., encompasses future investments in AI, semiconductor, energy, and manufacturing sectors. The statement emphasized that it would “substantially increase” the UAE’s existing U.S. investments. Not all details were new – Reuters noted that some deals in the framework had been previously announced, implying the $1.4T aggregates ongoing and future plans. Crucially, one entirely new component was unveiled: Emirates Global Aluminium (EGA) will invest in building a new aluminum smelter in the U.S., the first new one in 35 years. This project stands out as an immediate tangible investment (likely a multi-billion dollar facility, potentially located in a U.S. Gulf Coast state to leverage cheap energy). Also highlighted was ADQ’s partnership with U.S. firm Energy Capital Partners to launch a $25B U.S.-focused fund for energy infrastructure and data centers – announced just days prior, it exemplifies the collaborative investment vehicles being formed. Another piece of the framework is ADNOC’s support for U.S. natural gas exports: ADNOC (Abu Dhabi National Oil Co.) via its investment arm XRG, had already committed to invest in NextDecade’s Rio Grande LNG project in Texas, a deal announced under the previous U.S. administration. All these were rolled into the “$1.4T package.” Politically, it was framed as a major win-win: the UAE diversifies beyond oil by investing in America’s tech and industry, and the U.S. gets a wave of capital to bolster supply chains and manufacturing. The news came with symbolic optics like photos of U.S. Secretary of State (Marco Rubio) with Sheikh Tahnoon in Abu Dhabi, underscoring the strategic nature of the deal.

Key Sectors and Projects: The UAE’s planned investments focus on areas that leverage the country’s existing strengths and its diversification ambitions:

Artificial Intelligence & Digital Infrastructure: The UAE has declared becoming an AI leader as a strategic goal (it even has a Minister of AI). To that end, a significant portion of the $1.4T is aimed at AI infrastructure in the U.S. – likely meaning investments in U.S. data centers, cloud computing, and AI research companies. One example is Project Stargate (referenced in U.S. White House materials), involving SoftBank, OpenAI, and Oracle announcing a $500B private investment in U.S. AI infrastructure – while not explicitly labeled as UAE, SoftBank’s Vision Fund 2 includes Mubadala capital, and G42 (Abu Dhabi’s AI firm) has partnerships with OpenAI, suggesting indirect UAE backing. The UAE’s G42 and its investment arm (42XFund) are actively investing in U.S. AI startups and biotech (via subsidiaries like Synapse and a new $10B tech fund as mentioned). Another facet is semiconductors: the UAE via Mubadala historically owned GlobalFoundries (a major chip manufacturer with fabs in the U.S.), and while Mubadala has since floated GlobalFoundries, it remains the largest shareholder. Under the new framework, UAE might invest in expanding U.S. semiconductor fabs or in chip design companies, aligning with the U.S. push for domestic chip production.

Manufacturing & Industry: The UAE’s diversification plan (e.g., Abu Dhabi’s “Operation 300bn” strategy) emphasizes developing heavy industry – the EGA aluminum smelter in the U.S. is a prime example. EGA is one of the world’s biggest aluminum producers (co-owned by Mubadala and Dubal); building a smelter in the U.S. suggests confidence in U.S. manufacturing and could fill a strategic gap (reducing U.S. reliance on imported aluminum, a critical material)reuters.com. This investment stands to create jobs in construction and operations (smelters employ hundreds and support many ancillary jobs). Another manufacturing venture could be in electric vehicles or batteries – there are reports that UAE investors looked into U.S. EV startups and battery plants (perhaps partnering with companies like Tesla or Rivian). Given the mention of “energy and manufacturing,” UAE funds might support building battery gigafactories or hydrogen electrolysers in the U.S. where the tech could later be imported to UAE.

Energy & Clean Tech: Energy has two sides for UAE: oil/gas and renewables. On oil/gas, ADNOC’s investment in U.S. LNG (NextDecade project) is notable – ADNOC in 2023 took a stake in a $$8 billion U.S. LNG project, marking its first major investment in North America’s energy sector. This aligns with the UAE’s strategy to ensure markets for its gas and be involved in global gas trade. On clean tech, Masdar (Abu Dhabi’s clean energy company) has been active in U.S. renewable projects (wind and solar farms, often in partnership with U.S. utilities). Under the new deals, expect UAE capital flowing into U.S. hydrogen production (UAE is keen on hydrogen and might invest in U.S. pilot projects for green hydrogen) and carbon capture technologies. Also, the UAE’s interest in space exploration (mentioned in MBZ’s White House meeting) could translate into investments in the U.S. space sector – e.g., Mubadala’s satellite company Yahsat could buy U.S.-made satellites or invest in U.S. space startups.

Infrastructure & Real Estate: Historically, the UAE (particularly Abu Dhabi) invested in U.S. real estate funds and infrastructure. ADIA has large stakes in U.S. prime office buildings and residential portfolios (though some have been rebalanced recently due to market shifts). The new framework’s focus on infrastructure might see ADIA or ADQ co-investing in U.S. infrastructure projects – for instance, highways, ports, or telecom networks, potentially through public-private partnerships. The ADQ-Energy Capital $25B initiative mentioned includes data centers, which are digital infrastructure but also a real asset play (building and owning data center facilities in the U.S.). Real estate-wise, UAE private developers like Emaar or DAMAC have occasionally looked at U.S. projects (DAMAC bought a plot in Miami in 2022). Emirates airlines indirectly invests in U.S. airports by funding expansions (like contributing to Orlando airport’s improvements) which though not equity stakes, demonstrate UAE’s holistic approach to making the U.S. more accessible for commerce.

Finance & Private Equity: The UAE’s sovereign funds often allocate capital to U.S. private equity firms as LPs. Mubadala has an office in New York focusing on direct deals and fund investments. For example, Mubadala committed funds to Silver Lake, Apollo, and others – enabling those firms to invest more in U.S. companies. In 2023, Abu Dhabi’s Chimera and Alpha Dhabi launched a $2B fund with U.S.’s Apollo for credit investments. These financial plays might not headline in political announcements but are part of the landscape (some of that $1.4T will simply be UAE money pumped into U.S. stocks, bonds, and funds). However, because the emphasis is on visible investments that “create jobs,” the UAE will likely highlight direct investments over financial portfolio moves.

Investment Vehicles: The UAE’s investments come from a constellation of sovereign funds and state-owned companies, primarily from Abu Dhabi (since Abu Dhabi controls the bulk of UAE’s oil wealth and SWFs) and to a lesser extent Dubai:

Abu Dhabi Investment Authority (ADIA): One of the world’s largest SWFs (estimated assets around $800 billion), ADIA traditionally invests for financial return with a long-term horizon. It has sizable U.S. holdings in public equities, real estate, and fixed income. ADIA usually doesn’t take an activist role but provides substantial capital. For instance, ADIA was a big investor in U.S. apartment portfolios (via GRE partnerships) and is reportedly a top-10 shareholder in dozens of U.S. blue-chip companies (via index investments). While ADIA might not be specifically earmarked in the $1.4T announcement, any broad increase likely involves ADIA raising its U.S. allocation by some percentage.

Mubadala Investment Company: Abu Dhabi’s strategic development fund (with ~$330B AUM). Mubadala is very active in the U.S. – it has subsidiaries like Mubadala Capital that manage funds partly focused on North America. Mubadala’s portfolio includes stakes in U.S. tech (it famously invested in chipmaker AMD years ago, and more recently in Waymo via SoftBank’s fund), U.S. life sciences (it owns pharmaceutical and medtech assets), and even U.S. sports (Mubadala sponsors the Silicon Valley tennis classic). Under the new initiatives, Mubadala could spearhead joint ventures in semiconductors or aerospace (given its experience with GlobalFoundries and Strata, an aerospace components firm).

ADQ: A newer Abu Dhabi fund (~$150B AUM) chaired by Sheikh Tahnoon, ADQ has taken over many government assets (airports, utilities) and invests strategically. ADQ was explicitly mentioned in the context of a $25B U.S. initiative in energy & data centers. ADQ, through its venture wing DisruptAD, also invests in U.S. startups. It may play a big role in food/agriculture investments (ADQ owns companies like UAE’s Agthia and might invest in U.S. agritech or food supply chains as food security is key for UAE).

Emirates Investment Authority (EIA): the federal UAE fund is smaller, but one notable arm is Emirates MGT (Emirates Marsa Investment) which recently was rumored to look at U.S. infrastructure deals. Not a major player compared to ADIA/Mubadala though.

State-owned Enterprises: Companies like EGA (Emirates Global Aluminium) – co-owned by Mubadala and Dubal – doing the smelter project; TAQA (Abu Dhabi energy co.) which might invest in U.S. utilities or power plants; Etisalat (e&) the telecom giant that might partner with U.S. tech firms (it hasn’t heavily invested in U.S. companies yet, but as it expands digital services it could acquire U.S. tech vendors). Dubai’s entities like DP World (ports operator) invested in the U.S. previously (it had to divest U.S. ports in 2006 due to political pushback, a famous case under CFIUS). Dubai’s ICD (Investment Corp of Dubai) has stakes in global companies including some U.S. holdings (for example, ICD was part of a consortium buying Chrysler Building in NYC in 2019).

Private sector and others: UAE’s wealthy business families sometimes invest in U.S. real estate or franchises (e.g., the Al Habtoor Group building a hotel in the U.S., or individuals buying stakes in tech companies via venture funds). These are comparatively small but add to the tapestry.

Flagship Projects & U.S. Partners: The UAE’s deep ties to the U.S. are visible through marquee projects and collaborations:

GlobalFoundries: Owned by Mubadala until recently, it operates major semiconductor fabs in New York and Vermont. This was a flagship UAE investment in U.S. high-tech manufacturing. Even after the IPO, Mubadala retains a controlling stake, meaning the UAE is literally producing a share of America’s chips – a strategic asset for both sides.

Masdar’s U.S. Renewables: Masdar (Abu Dhabi’s clean energy co.) has invested in multiple U.S. renewable energy farms (wind in Texas, solar in California, etc.) often co-owning them with U.S. firms like EDF or EDP. These projects, totaling in the hundreds of MWs, are a quiet success story of UAE green investment fueling U.S. clean energy growth.

Space Collaboration: The UAE and U.S. are partners in space exploration (the UAE astronaut flew to the ISS via SpaceX in 2023). UAE invests in U.S. aerospace tech – e.g. Mubadala’s Strata provides parts for Boeing and Airbus. There’s also talk of UAE investing in U.S. NewSpace companies or perhaps partnering on the Artemis program’s components.

Academic and Cultural ties: Similar to Qatar’s, but less controversial – NYU has a campus in Abu Dhabi funded by UAE; Masdar Institute partners with MIT; and the UAE funds some U.S. think tank programs. These aren’t direct investments, but they represent the UAE’s integration with U.S. knowledge networks, which often complement investment goals (e.g., attracting U.S. tech talent to UAE’s hubs).

Bilateral Agreements: The U.S. and UAE have multiple forums – the U.S.–U.A.E. Business Council is very active, promoting investment both ways. There’s a Trade and Investment Framework Agreement (TIFA) since 2004 which provides a platform to address issues. Additionally, a new partnership called the U.S.-UAE “Partnership for Accelerating Clean Energy” (PACE) was announced in late 2022, with the UAE committing $100B in clean energy investment worldwide, including substantial in the U.S. This indicates that some portion of UAE’s $1.4T framework will go specifically to clean energy projects under PACE (like funding renewable generation, nuclear energy cooperation, and carbon capture in the U.S.). The Comprehensive Strategic Partnership announced in 2022 elevated ties and explicitly mentioned investing in critical technologies and infrastructure as pillars.

In summary, UAE investments in the U.S. are broad-based and significant, reflecting the UAE’s role as not just a trade partner but an increasingly pivotal investor in America’s future industries. The May 2025 commitment of $1.4 trillion – while an aspirational envelope – underscores the UAE’s intent to be one of the top foreign investors in the United States. If realized, it would transform the scale of UAE’s involvement from tens of billions to hundreds of billions in tangible assets, making the UAE a household name in projects across America (from factories to tech campuses to energy facilities). Such deep economic intertwining complements the UAE’s defense alliance with the U.S. and its positioning as a moderate, innovation-driven hub in the Middle East.

Motivations and Strategic Objectives (Gulf vs. U.S. Perspectives)

Understanding why these investments are being made is crucial, as they are driven by strategic calculations on both sides:

Gulf States’ Motivations:

Economic Diversification and Returns: At the core, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the UAE seek to diversify their economies away from oil and gas dependence. Investing in the U.S. – the world’s largest economy and innovation leader – offers access to sectors that the Gulf needs for its future (be it AI, biotech, advanced manufacturing, or alternative energy). Financially, the U.S. provides stable returns and deep capital markets; Gulf sovereign funds can earn income to sustain their domestic development and future generations. Saudi’s PIF, for example, is “driven primarily by economic considerations” in many of its U.S. equity investments, aiming to profit from growth industries. Qatar’s and UAE’s surpluses from recent energy windfalls can be productively deployed in high-growth U.S. assets rather than sitting idle. Also, big-ticket U.S. investments often come with technology transfer or training that can be brought home (e.g., by investing in a U.S. aerospace company, a Gulf fund might secure internships for its engineers).

Advancing National Visions: Each Gulf state has a national vision blueprint (Saudi Vision 2030, Qatar National Vision 2030, UAE Vision 2021/2071) that highlights developing knowledge economies, high-tech industries, and world-class infrastructure. Direct investment into the U.S. often ties back into these visions. For instance, Saudi investing in Lucid Motors (EVs) and U.S. entertainment (through its sports fund) feeds into Vision 2030 goals of creating local auto industry and entertainment sectors. Qatar’s investment in education (funding U.S. universities, etc.) aligns with its goal of becoming an education hub. UAE’s focus on AI and space with the U.S. directly supports its ambition to be a global tech hub. In short, by investing in leading U.S. companies or projects, the Gulf states plug into global value chains and can later import know-how or co-develop projects at home.

Geopolitical Influence and Soft Power: Deploying vast capital in the U.S. also buys influence and prestige for Gulf countries. High-profile investments make these states important stakeholders in the U.S. economy, potentially translating to political capital. For example, Qatar’s billions in U.S. real estate, businesses, and donations to universities have been noted as a way to “purchase access to [U.S.] corridors of power”. Owning stakes in influential companies or funding cultural institutions can give Gulf leaders soft leverage – it’s easier for them to get a friendly hearing in Washington if they are known for supporting U.S. jobs and growth. The Middle East Forum’s analysis pointed out that Qatar’s strategic spending in the U.S. (over $40B across business, real estate, education, think-tanks) enhances its image and influence, even as some of its policies diverge from Western values. Similarly, Saudi Arabia hosting an American golf tour (via LIV) or the UAE’s investments in U.S. tech create networks of influence. In a region where global influence was traditionally through oil or ideology, investing in the U.S. is a form of “geo-economic” diplomacy, showcasing Gulf states as partners in prosperity.

Security and Strategic Alignment: There is a symbiotic logic: by heavily investing in the U.S. economy, Gulf states aim to cement the U.S. as a long-term security ally. The thinking is that if Saudi/Qatar/UAE money is helping build factories in American towns and creating American jobs, U.S. policymakers will be more inclined to preserve strong ties and defend those countries’ interests. This is particularly relevant for Saudi and UAE, who see the U.S. as a security guarantor against threats (Iran, extremism). Their investments come alongside record arms purchases, reinforcing an interdependence – “we invest in your economy, you help guarantee our security.” For Qatar, which hosts a major U.S. air base, investment is also a way to show it’s a valuable ally not just militarily but economically (especially important as Qatar navigates complex relations with neighbors and the U.S.). Moreover, by investing in U.S. defense tech firms or setting up co-production, these states aim to ingratiate themselves into the U.S. defense-industrial ecosystem, making it less likely the U.S. would cut them off in a crisis.

Hedging Global Competition: Gulf countries are mindful of the rising influence of China and Asia. They do invest in China as well, but U.S. investments serve as a hedge to maintain balance. If China is investing in the Gulf (as it is, via the Belt and Road), Gulf states reciprocating with big U.S. investments helps ensure they are not overly dependent on one bloc. It’s a form of strategic hedging – enjoying strong ties (and investment partnerships) with both East and West. For example, the UAE can leverage its $1.4T U.S. pledge to also negotiate favorable terms with China or Europe by demonstrating it has options.

United States’ Motivations:

Economic Benefits and Jobs: The United States welcomes Gulf investments primarily because they stimulate economic growth and job creation domestically. Large infusions of capital from Saudi/Qatar/UAE can finance new factories, infrastructure, and business expansions that might otherwise stall for lack of funding. The White House in 2025 explicitly touted how these deals “bolster American manufacturing and technological leadership” and put America on track for a “new Golden Age” of innovation. For instance, Qatar’s aircraft purchase supports over a million U.S. jobs in Boeing’s supply chain, and the UAE’s aluminum plant will create hundreds of permanent manufacturing jobs in addition to construction jobs. In an era where the U.S. is competing to reshore industry and update infrastructure, Gulf capital provides a welcome boost. Additionally, Gulf sovereign funds often invest in ventures that struggle to find U.S. private funding due to size or risk – for example, investing billions in an LNG terminal or a cutting-edge tech fund. This aligns with U.S. objectives like energy security (financing LNG export means more U.S. gas production capacity) and tech advancement (capital for AI and semiconductor plants).

Strengthening Alliances & Middle East Stability: Encouraging allied Gulf states to invest heavily in the U.S. is also a way for Washington to bind those allies closer and ensure their continued alignment with U.S. interests. As one expert noted in early 2025, Trump sought to get “trillions of dollars” out of the Gulf countries, implying that massive economic intertwinement was a goal in itself to solidify partnerships. These investments can be framed as win-win: allies get economic ties, the U.S. indirectly secures their loyalty. Also, a Gulf that is economically successful and outward-investing is one that is stable and less likely to foster extremism or conflict – so U.S. policymakers see supporting Gulf diversification (even via receiving their investments) as conducive to regional stability. When Gulf nations invest in the U.S., they also have a stake in a stable international order that the U.S. leads.

Countering Rivals (Great Power Competition): In the context of U.S.-China competition, having Gulf states pour money into the U.S. serves to counterbalance China’s global investment push. The U.S. would prefer Saudi and Emirati capital to flow into American high-tech industries rather than into, say, Chinese projects. Indeed, some of these deals can be seen as victories against Chinese influence: e.g., persuading the UAE to build an aluminum smelter in the U.S. (using presumably U.S. or allied tech) rather than deepen its integration with Chinese industry. Also, if the U.S. can satisfy Gulf states’ investment objectives, they might be less tempted to participate in initiatives like China’s Belt and Road or to let Chinese tech into their 5G networks, etc. The U.S. has already leaned on UAE and Saudi to limit Chinese military or tech footholds (like the UAE reportedly halted a Chinese base project on its soil under U.S. pressure). By engaging them economically, the U.S. keeps them in its orbit.

Financing American Infrastructure and Deficit: On a more macro level, Gulf investments help finance the U.S. economy’s needs. Gulf countries have historically been big buyers of U.S. Treasury bonds (recycling petrodollars to fund the U.S. deficit). The 2023–25 trend takes it further – instead of just passive bonds, Gulf money is funding tangible projects. This aligns with U.S. initiatives like the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act; if foreign sovereign funds co-invest in these infrastructure upgrades, it eases the burden on U.S. public finances. There’s also synergy with investment promotion programs – for example, the SelectUSA program has actively courted Gulf investors to invest in U.S. states and create local jobs. States like South Carolina, Ohio, Michigan often compete to attract automotive or tech investments; a sovereign fund deciding to build a facility can rejuvenate local economies. U.S. officials know that Gulf funds have deep pockets – during times when domestic investment might be constrained (say, if U.S. interest rates are high), foreign investment from Gulf is highly advantageous.

In summary, Gulf and U.S. perspectives converge on many points: both want economic growth, innovation, and strong ties. The Gulf sees investment as a means to secure a prosperous, knowledge-based future and international clout; the U.S. sees it as a means to rejuvenate industries, outcompete rivals, and lock in strategic friendships. There is a sense of mutual reinforcement – for example, as one analyst succinctly put, many of PIF’s U.S. investments tie into Saudi’s domestic ambitions while also benefiting U.S. sectors like gaming, tech, and AI. Each successful deal ideally creates value in both societies, which is a selling point leaders use to justify the partnership internally.

Economic Impact Assessment

The influx of Gulf investments into the U.S. from 2023–2025 carries significant economic implications, both in the short-term and long-term, on multiple fronts:

Impact on the U.S. Economy:

Job Creation: Perhaps the most immediate and politically emphasized impact is job creation in the United States. Many of the investments are explicitly tied to new U.S. jobs. For instance, the Boeing-Qatar Airways $96B deal is expected to support 154,000 U.S. jobs annually, totaling over a million jobs over the course of the contract. The rationale is that large orders keep assembly lines running and suppliers busy (from Boeing’s factories in Washington and South Carolina to GE’s engine plants in Ohio). Similarly, the UAE’s EGA aluminum smelter project will create not only direct jobs at the smelter but also indirect jobs (in construction, maintenance, supply of raw materials like alumina, etc.). Saudi Arabia’s investment in U.S. data centers (DataVolt’s $20B) will lead to construction and tech jobs across the locations chosen. Moreover, initiatives like Saudi’s funds for energy and defense will likely inject capital into American startups and expanding firms, enabling them to hire more engineers and skilled workers. The White House has been keen to quantify these: e.g., the Saudi deals package was hailed for “creating high-quality jobs across the United States”, the Qatar Boeing deal for supporting over a million job-years, and the notion that each investment fund will drive innovation and create high-quality jobs in the U.S. Areas poised for job growth include manufacturing (e.g., reopening or expanding factories, like the announcement of previously shuttered plants being revived – such as Stellantis’ re-opening an Illinois auto plant with Gulf-supported demand for vehicles), construction (for new facilities, infrastructure), and tech R&D (AI and quantum ventures funded by Gulf money will hire researchers in the U.S.).

Industrial Growth and Capacity: These investments significantly bolster U.S. industrial capacity. The new aluminum smelter project by UAE will enhance domestic production of a critical material – currently the U.S. imports a large share of its aluminum. Doubling domestic output (as stated) improves supply chain resilience, and possibly can reduce input costs for U.S. manufacturers (auto, aerospace industries need aluminum). Likewise, investments in semiconductor manufacturing by Gulf funds (e.g., if Mubadala invests in new chip fab expansions) help expand capacity in a sector where demand outstrips supply. In energy, funding from Qatar and UAE for LNG and other infrastructure increases U.S. export capacity, which can have macroeconomic benefits – more exports improve trade balance and spur related upstream jobs (more gas drilling in this case). Also, co-investment in renewables and grids can accelerate the clean energy transition by building more projects than domestic funding alone might allow. All these add up to a strengthened industrial base, aligning with the U.S. goal to rejuvenate manufacturing.

Innovation and Technological Advancement: Gulf investments are targeting high-tech sectors like AI, quantum computing, aerospace innovation, biotech, and defense tech. The infusion of billions into startups or research-intensive projects can speed up innovation cycles. For example, the $1B Qatar-Quantinuum quantum JV will support cutting-edge research and potentially breakthroughs in quantum tech that American companies or universities are working on – effectively adding an extra funding stream that accelerates progress. Similarly, if Saudi’s tech fund invests in a range of U.S. AI startups, some of those may achieve technological milestones (in autonomous driving, cybersecurity, etc.) faster with ample capital. This benefits the U.S. by maintaining its edge in these critical technologies. Furthermore, partnerships often involve knowledge exchange: U.S. firms partnering with Gulf money might collaborate with Gulf research institutions (e.g., IBM partnering with UAE’s AI ministry on certain projects financed by UAE). The net effect is additional R&D funding in the U.S. and more experimentation, which can lead to new products, patents, and even new industries.